Contents

– Insight from Coty counsel

– Analysis from four US lawyers

– Insight on legal impact and next steps

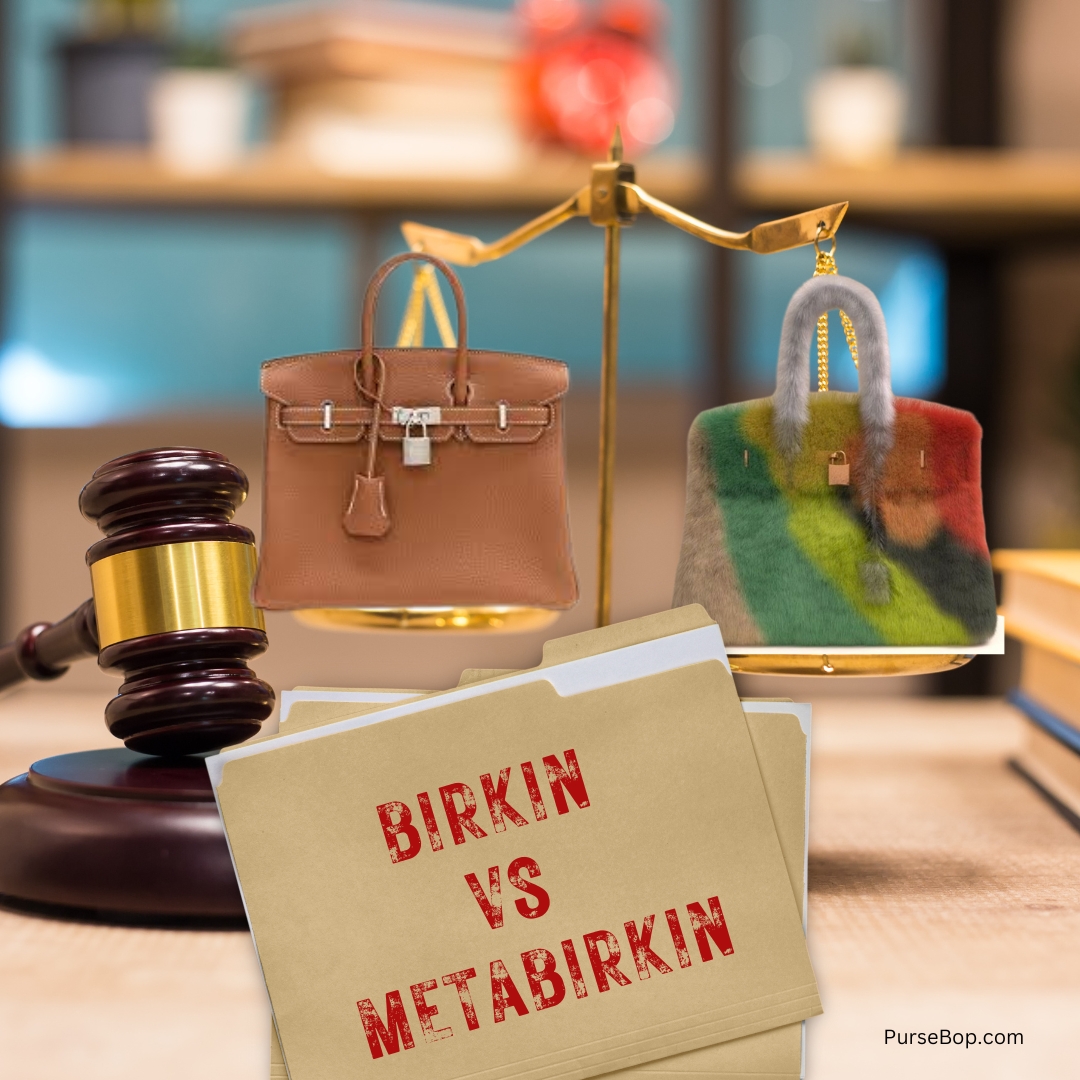

A victory for luxury apparel company Hermès has increased the confidence of lawyers in enforcing trademark rights in the non-fungible token space, say sources.

A jury ruled on Wednesday, February 8, in the District Court for the Southern District of New York that artist Mason Rothschild had infringed the apparel business’s ‘Birkin’ trademark when he sold ‘MetaBirkin’ virtual handbags as NFTs.

The jury also found him liable for trademark dilution and cybersquatting.

It came despite Rothschild’s defence that his NFTs were an artistic commentary on the fashion industry’s history of animal cruelty and an embrace of fur-free initiatives, and that they therefore should be protected under the first amendment.

Joseph Conklin, global deputy general counsel at beauty company Coty in New York, says this case gives him more confidence because it provides guidance on what a jury will consider important in determining whether a well-known mark is likely being used in an infringing or dilutive way.

Others agree that the jury verdict is good for trademark owners.

Michael Kasdan, partner at Wiggin and Dana in New York, says he’s not sure whether the decision will change the status quo that much, but a ruling in the artist’s favour would have had a bigger impact the other way.

“It’s a sigh of relief for brand owners that Hermès won the case,” he says.

Some of the points that Judge Jed Rakoff made were also favourable to companies that want to prevent NFT creators from playing off their brands.

Kasdan notes that the judge was interested in the subjective intent of Rothschild – whether the artist was more interested in commercialising or profiting than in artistic commentary.

Kasdan says this analysis will be frustrating for artists who will argue that there’s not a clear line between art and commerce given that they want to make money through their art.

But he adds that trademark owners have expressed frustration that someone can play off their brands, cause confusion and get away with it by calling it art – so Rakoff’s analysis is good for them.

There’s also the fact that Rakoff had excluded art critic Blake Gopnik, who would have been the defendant’s art expert, from the case.

Ron Dreben, partner at Morgan Lewis in Washington DC, noted that the judge had stated that the expert’s opinion needed to be based in solid methodology and the results had to be replicable by other experts. The judge didn’t think Gopnik’s testimony would meet that standard.

“If you don’t have an expert saying it’s art, it’s difficult to establish that,” he says.

Though Rakoff didn’t allow Gopnik to testify, he came to some conclusions in the defendant’s favour.

He stated in the jury instructions that it was undisputed that the NFTs were “in at least some respects works of artistic expression”.

Despite this, the jury determined that the first amendment protection didn’t bar liability.

Some counsel think the jury may have gone too far, however.

Matthew Asbell, partner at Offit Kurman in New York, argues that it was hard to come to the right decision in this case, but it was pretty clear that Rothschild’s works weren’t virtual Birkin bags and that they were a form of commentary.

“You need to find a balance. You want brand owners to be able to enter the world of NFTs, but they shouldn’t be automatically entitled to enforce against NFTs for artistic works just because there’s a trademark reference in them,” he says.

Parties that would like to enforce against NFTs for artistic works that reference their trademarks can learn a few tricks from this trial if they’re in similar situations.

Dreben at Morgan Lewis notes that the parties disagreed on a survey over whether NFT buyers were confused. The apparel company had determined that 18.7% of potential purchasers were confused. But the defendant calculated, based on the same survey, that just 9.3% were.

Dreben says that although it’s unclear how much the jury was influenced by the survey evidence, the case is a good reminder that brand owners have to be ready for their surveys to be challenged and that they should make sure the surveys are as defensible as possible.

The plaintiff also did a good job at explaining its position, say sources.

Anna Naydonov, partner at White & Case in Washington DC, says Hermès was able to successfully explain why the NFTs were an infringing product to which traditional trademark infringement considerations would apply, as opposed to something drastically different.

Other brands will have to follow the same course, she says.

The issue isn’t entirely resolved, however.

Kasdan at Wiggin and Dana notes that the jury had asked the judge what would happen if it was unanimous when deciding trademark infringement and dilution but divided over whether the artist was protected from liability because of the first amendment.

He notes that the judge told them to keep deliberating, but the question indicates that members were struggling with the right balance and that lawyers and courts might need more guidance on this issue.

This case will also very likely be appealed to the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, which could potentially overrule the district court.

Dreben at Morgan Lewis says it may be hard for the defendant to succeed on appeal, however, because the case is very fact-dependent and the judge has a lot of discretion over what evidence should be admitted.

Lawyers could see more clarity when the US Supreme Court rules on Jack Daniel’s v VIP Products, in which it will hear oral arguments in March.

The court will determine whether dog toys using the Jack Daniel’s trade dress and the words ‘Bad Spaniels’ should be subject to the same likelihood of confusion analysis as other items under the Lanham Act or if they should receive heightened first amendment protection as an expressive work.

Dreben says SCOTUS’s opinion in this case could be relevant to the MetaBirkin outcome if the case is appealed, but it’s hard to say how it will all play out.

Even if the jury’s verdict gives brand owners more certainty in certain instances, they will still find it challenging to enforce against NFTs in others.

Naydonov at White & Case points out that it was very clear who the defendant was in this case, but there will be more and more situations in NFTs and the metaverse in which it’s very hard to locate who’s creating allegedly infringing items.

Brand owners may only be able to find crypto wallet information, for example. The Department of Justice and regulators have become good at trying to identify who’s behind these, but that could be very hard for regular brands enforcing their marks, Naydonov notes.

“They’ll have no idea who’s behind it,” she says.

It’s clear that there’s still a lot of uncertainty on how best to enforce rights in the NFT space, as well as in the intersection between NFTs, trademarks and the first amendment.

But brands that want to enforce in the area at least have some evidence that the law will be on their side, for now.

Source: ManagingIP

Keywords: Trademark Infringement

RESOLVING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS DISPUTES QUICKLY AND EFFECTIVELY

PROTECTION OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS SECURELY

FOR DOING BUSINESS STRONGLY, DEVELOPING SUCCESSFULLY

ELITE LAW FIRM – 255 Hoang Van Thai Str., Thanh Xuan Dist., Hanoi, Vietnam

Tel: 0243 7373 051 | Hotline/Whatapps: 0988 746 527 | Email: info@lawfirmelite.com